American Bandstand

This writing was originally written for Prejudice: Stories about Hate, Ignorance, Revelation, and Transformation, edited by Daphne Muse and published by Hyperion Books for Children in 1995.

I hated nice weather. My mother would make me sit on the stone stoop of our brown apartment building after the school bus dropped me off, while she gossiped with the neighbors. She said it would do me good to get a little sun—I was so pale and skinny.

“But Ma,” I whined, “I want to go up and watch ‘American Bandstand.’” “Bandstand” was to the ‘60s and ‘70s what “Soul Train” was to the ‘80s and MTV’s “The Grind” is to the ‘90s.

“It will still be on by the time we go up. Look, your sister will be home from school in a few minutes and I’ll send her to the candy store to get you a chocolate malted.” My mother was not above bribery.

So I sat listening to the droning voices being carried into the air as the women talked about the fruit in season at the grocer or the sale on bathing suits at Alexander’s. I cooed at the babies awake in their strollers and felt pleased with myself that I could make them smile and laugh—they weren’t old enough to know I was different. And I watched as the kids walked past in droves as they were let out of neighborhood schools, the younger ones who would stare at me as their mothers ushered them on and the older ones who’d try not to notice me at all. I tried to ignore it all.

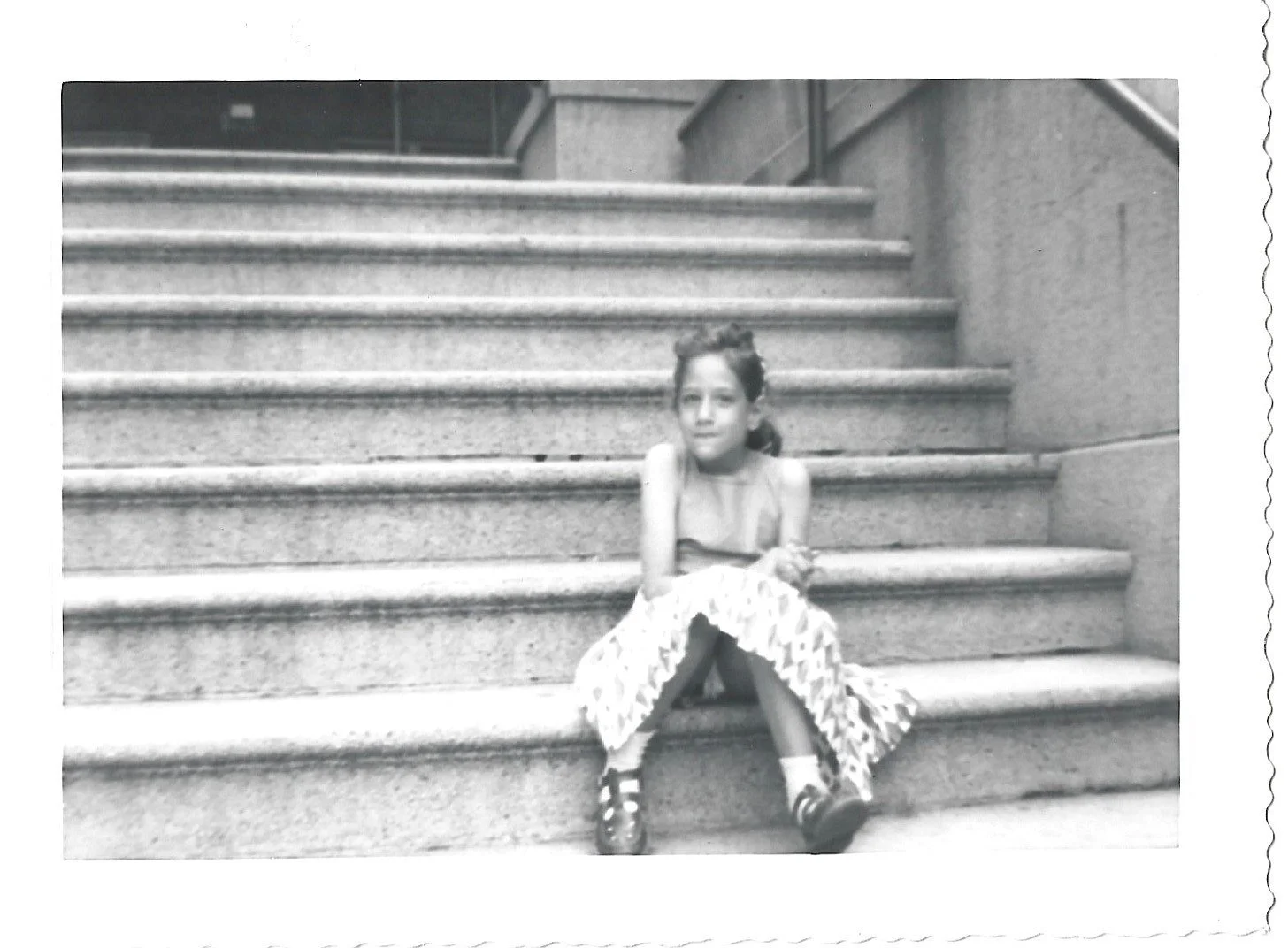

Young Denise, 7 or 8-years-old, sits on the steps in a dress with a wistful look on her face.

I would reach over to my navy blue and red plastic bookbag sitting next ot me on the steps and pull out a book, usually a Nancy Drew or, if my book report was due soon, one of the classics—a Mark Twain or Louisa May Alcott. Reading had its purposes—keeping me occupied and, by burying my nose in a book, I thought I could forget that Leslie Strom was on her way and I wouldn’t have to see her snub me. Only it never worked. I could always hear her coming—step-clump, step-clump, on the concrete sidewalk—even above the kids’ screechy voices and the heavy car traffic of the Grand Concourse. Step-clump.

“There goes Gimpy again,” I grumbled one day to Shelley, not loud enough for Mommy to hear.

“You know her?” My sister was surprised.

“We ride together in the same van to the Carolians’ on Saturdays. Yech.” I felt much the same about the Carolian Club as I did about the sun, but my mother insisted it was good for me to go. Yet if I had to choose between the two, I’d rather fry in the sun. “She never speaks to me in the van, either.”

My sister offered compassion: “Hey, maybe one day, I’ll run upstairs and throw a bucket of water out the window when she passes by.”

I chuckled. Shelley could think such wicked thoughts. I wished one day she’d really have the guts to do it. I could just imagine Leslie caught in the cascade—her carefully combed flip flopping, while water dripped from her stringy bangs and down her upturned nose. It would serve her right—that polio gimp.

I didn’t like her snubbing me, but I understood it. I was just letting my jealousy get the best of me. Oh, I wasn’t jealous because she only walked with one leg brace while I walked with crutches and double-leg braces connected by a pelvic band—although my braces weighed about three times as much as hers. They only really bothered me when the weather was hot and the leather bands holding my legs in place stuck to my skin, or when, as a growing eleven year old, I would outgrow them every four to six months—the pelvic band would press into my hips and irritate the skin covering my pelvic bone until the readjustment could be made. Yet, besides holding up my knee socks, my braces gave me a steadiness, a feeling of security and brief moments of pleasure, feeling such heavenly relief and freedom when I took them off at night. No, it wasn’t her brace or ability to walk better…

It wasn’t that she was able to go to a neighborhood school, either. I got more attention in the special unit I was bussed to everyday than I would have in a regular classroom. All my teachers (of which I only had three since kindergarten) were very impressed with me, and why not? I was smarter and cuter than the other handicapped kids; in the sixth grade, I was reading at a high school level and I was still blond and had a small nose. My mother always made sure I sparkled when I went to school in the morning (not that I’d come home the same way)—a little doll, they called me, since I was small and fragile-looking; they even remarked that when I sat still at my desk, you couldn’t tell there was anything wrong with me. So what if the other kids at school didn’t like me—the ones my age teased me because I was teacher’s pet, and the kids in my class—teenagers—didn’t want a little squirt hanging around. No matter, adults were more important than those snotty kids; they appreciated me. If I went to a neighborhood school like Leslie, I’d just get lost in the crowd.

No, what really bothered me about Leslie was that she was acceptable—her, and the clique she hung out with on Saturdays. True, the girls were a little older—twelve or thirteen—but the fact of the matter was, older or younger, they could all do whatever they wanted to. They’d get permission to leave the clubhouse and hang out at the corner hamburger joint. They’d get the leads in every drama group production. And none of the staff ever “found” them when they hid under the stairwell smoking cigarettes. They were doing just what was expected of them, because they only had polio—a mere inconvenience that surely didn’t stop any of them from being average kids. After all, they didn’t have to just sit still at their desks to look like there was nothing wrong with them—just sitting down ANYWHERE would do.

The polios—they were always at the top of the ladder, while I was on the bottom rung, because I had cerebral palsy (c.p.). The I.Q. tests didn’t matter; any movements in your body that you couldn’t control, speech that was slurred or slow, placed you on the bottom. No matter how I tried to climb up that ladder I still had the wrong disability. I hobbled too slowly to go with them to the candy store—even if they wanted me to, which, of course, they didn’t. I’d lip a cigarette if I took a drag, since my mouth always seemed to have an excess of saliva which escaped down my chin if I didn’t remember to swallow. And then there was drama…

Drama was the one activity I wanted so desperately to be in. I knew I’d be good; I was such a natural—I could have a smile on my face even when I was miserable, make people laugh with my “wonderful sense of humor,” poking fun at myself before others got the chance: “I walk so slow even the Tortoise could beat me in a race.” I was a great actress—alone in my room—playing out romantic scenarios: princesses, captured by tyrants, rescued by handsome princes. I told myself my speech impairment didn’t matter; when people really listened, it wasn’t hard to understand me (my speech therapist even said so): if I were up there on stage, my audience would have nothing else to do but listen.

Still, I wouldn’t dare try out for a part. I could just hear what would be said about me: “She’s making a fool out of herself, just like the rest of them.” Then the head of the Carolians would get wind of it and note in my file: “The child is immature and has an unrealistic view of her limitations. She does not accept her handicap.” Inevitably, the comment would appear on my school, medical and camp records and I would be lumped together with all the other c.p.’s. I couldn’t let that happen. So, I proved that I was not only smart, but knew my place, too—I joined the club newspaper.

My mother’s voice took me out of my silent lament: “Shelley, I want you to go get Neisie a malted.”

“Aw, Ma, send one of the other kids, send Nancy, she’s just hanging around,” protested my chubby sister, spalling her books down on the stone stoop. “I told Harriet I’d meet her at her house.”

It was always Harriet, or Alice, or Barbara. It was only me as a last resort—on weekend mornings when no one else was around. I knew she’d rather play with kids her own age but I was only two years and nine months younger and, I thought, a lot nicer than any of her friends—they were always so snotty. They’d only let me play with them on rainy days when their mothers gathered in our apartment to play mah-jongg.

The kids would go off into my parents’ bedroom after the women chased them away for pestering them at the game. My mother, like the others, would be so glad to not have them breathing down her neck that she’d give the kids permission to do anything—play with make-up? “okay”; wear old dresses and high heels? “alright”; jewelry? “only costume”; and she’d call after them, “Let Neisie play.”

On all fours—my way of getting around without my braces (a wheelchair was unheard of; my mother was afraid I’d start depending on it too much)—I’d half hop, half creep into the bedroom. They would be all dressed up in pinks and blues, fake pearls and rhinestones.

“Here,” one of them would say, throwing the ugliest dark, ragged housedress over me. “You can be the wicked witch or the evil stepmother.”

“Can’t I be the fairy godmother?” I asked, already blinking back stinging tears.

“Nancy’s the fairy godmother.”

“You always let her be that,” I pouted. They were always nicer to Nancy. Not that they really wanted to be—they were just scared of her mother: Pearlie could intimidate them with just one look. “Why am I always the evil stepmother?”

“Because we said so… And if you don’t like it, you won’t play,” came the final ultimatum.

It was no use looking to my sister for help; she stayed silent. I knew if I cried to my mother, she’d yell at Shelley, who would take it out on me. Besides, my mother was no Pearlie when it came to discipline; she’d just end up trying to make me understand, “Neisie, kids are cruel.”

So, I played the evil stepmother, ordering them to mop the floors and wash the dishes. They, of course, ran away, clunking off in oversized high heels. I followed after them, trying not to get my knees black-and-blue thudding them down too hard on the bedroom’s linoleum floor, or get splinters in my hands as I crept over the wooden hump of the doorway, or get rug burns from creeping on the living room carpet.

I couldn’t keep up with them; my legs kept getting caught in the stupid old housedress. Soon, a familiar muscle in the back of my neck would go into one quick spasm, in protest of all my tensely driving motion. The cramp jerked my head back, lasting no more than a second or two, but the pain was so deep that it sent hot shivers up to my head and down my spine. No one was paying attention to notice, so I would just sit there until the funny tingling went away. All that remained was my headache, which had really started before the chase. I’d have to ask my mother for aspirin and then go lie down. Dress-up time was over anyway; the kids were playing 45’s.

I had just slurped down the last of the malted that Nancy had volunteered to get for me because Shelley had gone off to Harriet’s. Looking up at my mother’s heavyset frame leaning against the stoop, I called until she heard me. “Ma? Ma?”

“What, Neisie?” Her head turned downward, but I couldn’t see her face—the sun was in my eyes. “You’re drooling, honey. You have to remember to swallow. You know what I always tell you?”

“Yes, Ma.” I recited with boredom: “When someone says I’m cute and takes my chin in their hand and feels that it’s all wet, they’ll go ‘blech!’” I made a horrible face.

“Right. And they won’t want to do it anymore.” She turned away for a moment to hear what the neighbor was saying.

“Good,” I mumbled to myself, “let ‘em keep their hands to themselves.” Still, I wiped my chin on the sleeve of my furry, red jacket before my mother saw me. Otherwise, she’d scold me, saying that the saliva would ruin the fur. I always did it, anyhow, when no one was looking—too lazy to pull out the hankie from my pocket. I finished seconds before she looked back at me. She waited while I swallowed.

“Ma, can we go up now?”

She clucked her tongue in mild exasperation. “Well, I guess I ought to start making supper soon, so we can eat before Daddy gets home. Just let me have one more cigarette.”

“But, Ma, I’ll miss Record Review.” They sometimes had it in the first half hour of “Bandstand” just like they do the top ten music videos on “The Grind.”

“Neisie, be patient,” my mother mildly admonished. “We’re going soon.” I threw my book back into my bookbag, snapped it shut and waited. It took her forever to finish.

Putting the butt out on the stone stoop and throwing it out into the gutter (for the street cleaners to sweep up in the morning), she gathered my aluminum crutches, my bookbag, her purse. She held it all with her right arm and hand, leaving her other limb free. I offered my right wrist, which her free hand grasped. She pulled me to my feet; it always took me a few seconds to stop wobbling. Then, using her body to steady her arm as she held me, we started the climb—22 stone steps on the outside, 20 marble steps to go once inside the hallway. By the time we were on the fourteenth or fifteenth marble step, the back of my legs would ache from the strain of carrying not only my own weight and the weight of my braces, but with the anticipation that in a few more steps, the grueling climb would be over.

Afraid that if I sat down on the kitchen chair, I’d be too wiped out to get up, I remained standing against the threshold of the kitchen and reached for my crutches propped against a nearby wall. Still catching my breath, I positioned the worn rubber armrests under my armpits and placed my hands tightly around the wooden handles. I hobbled my way through the long foyer to the living room (always filled with the musty film of cigarette smoke) and into the rectangular, blue-walled bedroom that I shared with my sister.

Immediately, I went to the television corner to switch on channel 7—”American Bandstand”—to be with Peggy and Justine and Bob and Tony and all my other friends. It didn’t matter that I wasn’t fourteen; I was mature for my age. I didn’t even play with dolls—I couldn’t dress them with all their buttons, buckles, and bows.

While the TV warmed up, I leaned my crutches alongside the window and plopped down on the bed. A Clearasil commercial was on followed by station identification giving me just enough time to rest and wipe the sweat form my forehead. Then I stood up and, holding on to whatever was steady in between, inched my way over to the closet. Grasping the doorknob, I was ready for the next cha-cha to Frankie Avalon’s “Venus,” or Lindy hop to Connie Francis’ “Lipstick on Your Collar.” I thought I wasn’t that bad, either—keeping time with the one-two but leaving the cha-cha-cha (or else I’d lose the beat) and, of course, I didn’t swirl around too much during the Lindy. I sat out the slow dances, since there was no shoulder to lean on; instead, I’d sing along with the Platters’ “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes”—I could keep up with most of the words—and was proud that I was able to carry a tune.

What a relief! No one stared. No one teased. No one disapproved—at least for the rest of the hour.